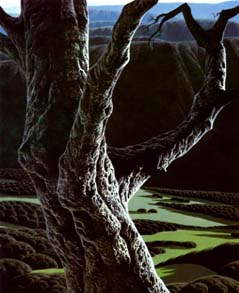

Eyvind Earle In one brief act of light and shade, nature can become striking and beautiful. A tree outlined by the setting sun--its bark scored deeper by shadows and its whole shape thrown into silhouette--is somehow more than a tree. Its image haunts us, and we look afterward to find the same magic in other trunks and branches. Photographers speak of sitting with camera and tripod all day to catch the right light, so that a picture will come alive. This is the light that Eyvind Earle captures. Earle's paintings and his serigraphs--screen prints that use paint films rather than inks--constitute a single body of work, for each of the prints he has produced through Circle Galleries and Hammer Publishing is based closely on a painting, and all but two are landscapes. Large geometric forms predominate: trees pressed flat, angular barns, the receding curves of an evening horizon. On these Earle imposes detail that is at once realistic and decorative, hinting here of the Flemish masters, there of the Japanese printmakers: scored bark, weathered planks, a tracery of shadows. This fusion of design with realism elevates his landscapes to a supernatural plane. The scenes are unmistakably Californian, yet we sense right away that they are not of this world. Gnarled branches may once have been twisted by wind or weather, but now the wind has died down, and the branches are still. Daylight, too, is curiously elusive. We never actually see the sun, yet Earle makes its presence felt by his use of shadow, often placing one large tree directly against his light source. The flattened trunk both shows off the brightness and obscures it. Over the years, critics have praised Earle's technique, noting his delicate glazes and meticulous attention to detail. Whether painting or printmaking, this artist shows that he has studied his medium and knows its every nuance. The real power of his art, however, comes from within. The French landscapist Pierre Henri de Valenciennes said it best: the greatest artists are those who, "by closing their eyes, have seen nature in her ideal form, clad in the riches of the imagination." Earle never just paints trees or shadows; he taps into their spirit and makes us feel the majesty of weathered oaks and the ghostliness of evening fingering its way across a field. Since 1978 Earle has lived with his wife Joan in a three-story house in the woods of Westchester County, New York. Just behind their home a stream plashes cheerfully over a weir. It's not the oak-dotted hills of California, but it's trees and water and dappled light. If he wanted to paint from nature, the artist would need only to step outdoors. But for years now the pictures, as he puts it, "have simply come out of me, like speech. Pattern develops by itself, and I let the creative spirit within do the creating." Inside the house every room is hung with paintings, turning the place into an art gallery. Any Earle painting is galvanizing at first sight; sixty-five of them are difficult to absorb. Yet a peacefulness follows the initial impact, and the artist appears to draw refreshment from contemplating his own work.

A converted three-car garage next to the house serves as Earle's studio, and already it is too small for his projects. In January 1982, as if to mark the beginning of a new year, he called a temporary halt to painting, assembled new screen-printing equipment, and began to make serigraphs entirely on his own, retaining Hammer Publishing as his distributor. Earle does his own color separations, as he has done since the early 1970s when he first contracted with Circle Galleries to make large prints from his pictures and distribute them nationally. Now he will control the whole process. "I want to do everything by myself," he declares. "The minute I get into something, I have to go the limit. If I stared to sculpt in clay or stone, I could so easily abandon all other forms of art. "The wonderful thing about screen printing is the inventiveness you can exercise with it. You can decide to do a thousand things as you print, like those thin, transparent glazes that shade from light to dark, or from a color to totally transparent. You can do things you couldn't do any other way. Try grading the color along a narrow line of paint! You can imitate a painting with a screen print, but you can't imitate a screen print with a painting. "I no longer copy paintings, but make up completely new pictures as I go along. Many times I add things, just as if I were painting, and I don't know what a picture's going to be like until it's done. Perhaps I should give the result a new name: screen paintings. These may be my art form, as wood-block prints were for the Japanese." Invited to describe his creative process more fully, the artist speaks in mystical terms. A student of yoga since the age of sixteen, he would begin work for many years by meditating, then rushing to the canvas to paint the beautiful scenes that appeared to him. "Now I don't have to meditate. I simply know that if I start with a pencil or brush, some higher intelligence will direct my work. There is a great force pulling us, and the more it manifests, the more creative we become. Art is an attempt to delve into this mystery, to pick one detail out of the infinitude of infinities and make it clear. "I don't try to convey an idea or emotion, and I'm not at all interested in art that is supposed to reflect our times. Greek art, which is as excellent today as when it was created, certainly doesn't reflect Greece 2,500 years ago. It simply is beautiful, superior possibly to any sculpture done since." As if to goad himself into perfecting his own art, Earle clips and keeps reviews of his contemporaries. "The colossal conceit of many prominent modern artists--such as most of the so-called New York Expressionists--is almost beyond comprehension. They are satisfied creatively by daubing huge canvases with sloppy slashes of raw color, empty of design or draftsmanship, void of emotional content. I have chosen at this time to devote my painting efforts towards perfecting to the utmost of my capacity whatever paintings I still possess or new ones I create. I shall strive to make them the sum total of my being." That's for the future; at present Earle has no plans to exhibit these oils. Instead he continues to produce his "screen paintings," and it is gratifying to watch the serigraphs enjoy financial and critical success in an age when loveliness has nearly become passé. Other artists may strive to impress with their anger or beguile us with nostalgia, but Eyvind Earle pursues beauty. This quest predates the Greeks, but Earle's craftsmanship and strength of vision make it compellingly his own. By Geoffrey

Blum |

|

|||||

Copyright © 2003 by Geoffrey Blum