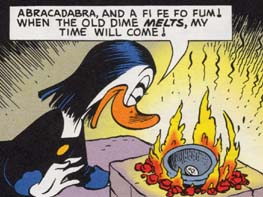

The Meaning of Magica There are few truly frightening duck stories. One thinks of "The Old Castle's Secret" and "Ancient Persia" (Donald Duck FC 189 and 275), but these are more shivery than scary. As Carl Barks himself pointed out, he was not writing for the EC horror comics. It's odd, then, that he should choose repeatedly to describe Magica de Spell in terms of fear; "terrible" becomes a tag word for her and her powers (Uncle Scrooge 38, 45, 48). On its own the word means little; it's a device to set the stage for a villain's entrance , like Scrooge's formulaic cry: "The Beagle Boys! The terrible Beagle Boys!" By and large, the Magica stories are free-for-alls built around farce rather than terror. Magica steals the Number One dime, Scrooge grabs it back, Magica summons up an enchantment to pry it loose, but the ducks persevere and the treasure returns safe and sound to its place in the money bin. Action consists of foof bombs and potions flying about, with a new sorcerous gimmick for each adventure, but there is seldom a focused menace of the kind that we find in the more obviously gothic tales. Occasionally Barks goes out of his way to tell us that we should be frightened. "Most of all I'm scared of her!" says Scrooge, pointing at a portrait he keeps taped to the vault wall, presumably as a warning to himself, a kind of memento magica. Donald shudders, and the narrator reinforces this mood: "Uncle Scrooge has good reason to worry! Magica de Spell is cooking up a gimmick that will make his wildest nightmares come true!" Eleven pages later, just in case the reader has grown complacent, the narrator cuts in with another warning: "Uncle Scrooge doesn't realize the terrible power of sorcery!" (US 48). This makes for good melodrama, but since Barks only tells us how to feel and never really frightens us, the shivers fall flat. We are left instead with something approaching camp. Besides, we take it for granted that witches are scary. Disney has built a film industry on that principle and glories in having created some of the nastiest hex-throwers in the history of animation. It's said that seats in the Radio City Music Hall had to be reupholstered after the premiere of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs because children wet themselves watching Queen Grimhilde turn into a hag. Barks has claimed, however, that he wanted Magica to be different: "Disney had witches in just about every movie they made, at least it seemed that way to me. So I thought, why not invent a witch? If I made her look kind of glamorous, with long sleek black hair and slanty eyes, instead of one of those fat, hook-nosed old witches, she could be an attractive witch." As it turns out, Magica is Barks' sexiest creation, but physical allure doesn't count for much in a duck comic. She gets to bat her eyelashes at Donald and at Scrooge's head clerk, and that's about it. Batting them at Scrooge would be pointless unless she were a thousand-dollar bill. The key to her character, Barks realized, would have to lie elsewhere. So when Magica sends Scrooge a valentine, it's not a come-on but a threat (Walt Disney's Comics and Stories 258). "Her good looks gave her an extra element of power," he explained. Crooks like the Beagle Boys and Flintheart Glomgold are goal-oriented. The burglars want Scrooge's money, and Flinty wants his title as World's Richest Duck. They may taunt Scrooge a bit in the course of battle, but their main objective is to take something from him and be done with it. At first this seems to be Magica's goal as well. With the dime in hand, she can forge a charm that will conjure up all the rich objects a compulsive shopper could want. As Barks put it, "She knows that if she took a barrel of Scrooge's money, why, in a little while it would be gone, but if she had that Old Number One Dime and made it into this very lucky amulet, she would have many barrels of her own money and would be the most powerful person in the world. She'd also be the richest." Note that word "power" again, with riches following as an afterthought. One gets the impression that Magica, for all her talk of living with "jewels and mink, and handmaids and butlers" (US 40), has an agenda quite different from the other villains. True, she wants to steal a precious object from Scrooge, but as the skirmishes pile up and we see how easily that object changes hands, gets snatched from the fire, even seems in one instance to slip unharmed through a meat grinder (WDC&S 258), it ceases to be the linchpin of Barks' storytelling and becomes a gimmick to promote wild action. We know that Scrooge will eventually get his dime back, and we know, with Scrooge, that the coin is just a symbol, "mere superstition," as he calls it (US 36). In later years Barks would regret having placed so much emphasis on it, writing in 1991 to Don Rosa, "The Number One dime should not be treated as a good luck charm. It contradicts the way Uncle Scrooge really made his fortune, but woe is me! I blatantly violated that rule in at least one story." The sorcery, too, is secondary, having no consistency beyond its sheer inventiveness. Barks, who favored science over superstition, clearly began with the intention of explaining Magica's tricks in mechanical terms. We see that foof bombs are chemical pellets stored up the sleeve (US 36), while the stun ray proves to be a battery-powered device carried in the same place (US 38). Physical transformations he depicted as switches of costume veiled by a pillar or a puff of smoke; a circus performer like Zippo could do them. In other words, Magica was a stage magician obsessed with trying one grand alchemical experiment. This approach worked for two or three stories, until the artist found he was painting himself into a corner. Then the spells became more exotic and the explanations more casual. Magica's transformation into a pig-faced mayor is never explained, just glossed over with a gesture implying that a modicum of science is involved: she pulls out a tape measure to get her new appearance right (US 43). A few issues later even the tape is dispensed with, and Magica turns into a bird with no other gloss than: "Didn't those yokels ever see a sorceress do tricks before?" (US 50). As the stories wore on, it never bothered Barks that he was making those tricks less plausible, because they never seemed to be a vital part of Magica's identity. A wand with the power to "fracture the cosmos" could be trivialized and used for a fanny gag thirteen pages later (US 43), while a spooky face-shifting spell might be washed off with ordinary soap and water (US 48). "It shows that sorcery is a superficial kind of thing in that respect," he said. Soon the sorceress stopped concocting her own enchantments and began to borrow from Circe and the ancient Greek gods. This gave the artist license to introduce even greater surges of fantasy, not to mention the archaeological themes he so loved. Foof bombs and stun rays might be reducible to nuts and bolts, but what scientist could unpick the powers of Zeus? So the spells and the dime are just props; we need to dig deeper for the dynamic between Scrooge and Magica. Larry Gooch's pseudo-Freudian analysis in The Barks Collector 24 is intentionally absurd , but he does have a point when he states that the sorceress behaves like a "hostile, punitive mother." She doesn't just want to take Scrooge's dime, she wants to deprive him of his power and identity as a way of feeling her own. "I'd like you better as a churchmouse!" she snarls, "the symbol of poverty!" (US 40). And again: "You're not the billionaire McDuck anymore! You're Scrooge McDuck, pauper!" (US 43). These attacks culminate with a story in which she actually steals Scrooge's physical identity in order to blackmail him: "Very well, McDuck! If you won't give me your old dime, you will never, never get your old face back!" (US 48). In each case, Barks' drawings suggest a maternal kind of terrorism. Scrooge cowers and tries to shield himself while the sorceress stands over him brandishing a wand, a potion, or an umbrella (WDC&S 265). Something of Daisy duck emerges in these moments. We recall the story in which Donald's girlfriend reduced him to nightmarish jitters by trying to display his needlework at her ladies' club (WDC&S 101), or the time she hounded him around Duckburg to enlist his aid for spring cleaning (WDC&S 213). It's no coincidence that Donald's nightmares featured huge, devouring mouths. Daisy, however, is unaware of the effect that she has on men, while Magica revels in her emasculating power, treating everyone in the same domineering way. She talks down to Scrooge's detectives (US 36), blitzes clerks and shopkeepers with her stun ray (US 38), even throws her weight around while walking down the street in disguise: "Move over, everybody! I'm on my way to get rich!" (US 43). Huey, Dewey, and Louie she dismisses as beneath contempt, calling them "little ducks," "children," and "pests." This is just the sort of treatment to make both kids and adults squirm. Much of Magica's threat--and much of the insult--is conveyed in her speech. That makes sense, since spells by their nature are verbl, but our sorceress manages to turn everyday conversation into a weapon. Other characters speak an easygoing sort of English that invites us in. It might be called colloquial were it not for the fact that Barks inserts clever little twists on words ("I have rugs that were made when Babylon was still a babe," US 50), gooses up clichés ("That offer has more strings attached than a starving spider," US 67), and regularly coins his own proverbs ("When riches rides the tides of fortune I drag no anchors," US 16). Still, in the mouths of the ducks, these sallies of wit sound homespun. We could almost be listening to Barks converse-as of course we are. Magica, in contrast, speaks a formal, self-regarding language marked by rhetorical gestures, poetic diction, scant contractions, and that unfailingly stilted nominative "It is I." With nobody present to hear her, she editorializes on her actions ("The little ducks I do not fear, but I will hurry nonetheless!") and addresses her surroundings operatically: "Ah, Vesuvius! Your breath is hot tonight!" (US 36). Not until her fifth appearance does she stoop to use the exclamation "Wak!" (US 40). In short, she talks as if she had a broomstick up her anatomy. Being a witch, she probably does. Andrew Lendacky in The Duckburg Times 23 has noted that Magica's lines "don't really tell us a lot about how Magica feels inside her skin, within the core of her being, at that moment." This is intentional. Magica uses words, like foof bombs, to throw up a smoke screen. As a result she distances herself not only from the ducks but from the average reader, since Americans instinctively distrust people who sound formal, cultured, or elite. I nearly said "old world," but Barks never explored this aspect of Magica beyond giving her a hot Latin temper and cracking a brief joke about Gina Lollobrigida (US 36). No, it's the note of superiority that sets people's teeth on edge. Look at the number of criminal masterminds in films of the 1960s who speak in just such a guarded, grandiloquent way, while the heroes slur their vowels and crack schoolboyish jokes. Hark to the clipped, imperious tones of Disney's greatest villains: Grimhilde, Maleficent, Captain Hook, and Cinderella's stepmother. Notice how many of them are women. So in the end we come back to sex. Magica de Spell is Barks' most frequently used and fully realized female, starring opposite Scrooge in seven adventures and two short stories. That's more than can be said of any male character except the Beagle Boys or Gladstone Gander. She is also the only recurring villainess in the duck comics. As such, she melds and intensifies stereotypes which the artist drew on for years, ones that might otherwise have stayed scattered more discreetly among a variety of characters. Like Daisy, she is a mother figure; like Madame Triple-X, a seductress (DD FC 308); and like Hazel (DD 26) and the hook-nosed hag who captures the Golden Christmas Tree (DD FC 203), she's a crone, a solitary, black-clad spinster, albeit a rather pretty one. These were the three basic roles available to women for more decades than bear remembering. Those who tried to step outside the pattern and build a new, more powerful identity were often stigmatized as witches. Note that Magica never locks horns with another woman. Aside from one panel in which she snaps at Fanny Featherbrain (US 45), she interacts with the men. If in doing this she assumed a traditional female posture, no eyebrows would be raised, but Magica seeks to play the boys' games for herself. That constitutes the greatest threat of all. Theft on the part of the Beagles or Flinty can be taken in stride; it's just another form of masculine competition. Theft on the part of Magica is portrayed as a cruel and unnatural act that reduces Scrooge to the level of a beaten child. When the sorceress steals his dime and turns his nephews into animals, McDuck doesn't throw his usual noisy tantrum about being "a poor old man." Instead we get a pathetic speech which is wrenching precisely because it's uncharacteristic: "This is the end of the line for my fortune!" sobs Scrooge. "With my old Number One dime gone, I'll no longer care what becomes of my other trillions of dimes! Nor will I care what becomes of me! My nephews are lost--all that I valued in the world is lost!" (US 40). In Magica's defense it should be pointed out that unflagging creativity goes far toward balancing occasional cruelty. In many ways she and Scrooge are a match: self-centered, determined, archaeologically adept, and bristling with imagination. Her operatic manner, off-putting in conversation, can as easily be turned to poetry. There is no finer soliloquy in the duck comics than Magica's ballet with the comets and meteors, which modulates from an orchestral richness of sound and image down to a single threatening hiss as she frightens the leaves of a potted plant (US 43). So much of her energy, like that of Barks, is rooted in language that she becomes incoherent when thwarted, spitting and sputtering like an overloaded circuit: "Sss! Fzt! Sft! Spt!" (US 36). As might be expected, the male villains suffer defeat with more poise. The Beagles cuss (US 51), try to cut a deal with the authorities (US 58), or simply grumble as they are marched back to their cells (US 28). Flinty collapses but retains enough spirit for a last defiant gesture (US 27). But Magica, bereft of her power as witch and artist, dwindles into a cheap stereotype, hissing and throwing rocks. It says much that "Race for the Golden Apples," a ten-page story in which Daisy threw similar hissyfits, was shelved by Barks' editors because it showed her "not acting in a ladylike manner." Presumably, only bad women behave in this fashion. Copyright ©

1997 by Geoffrey Blum |

|

|||||

Copyright © 2003 by Geoffrey Blum