| |

|

Surfing the Whirlpool

Surfing the Whirlpool

By October 1953, when

he finished inking "Tralla La" and sent the story off

to his publisher, Carl Barks had some of his greatest work behind

him. "Lost in the Andes," "Ancient Persia,"

"The Golden Helmet"--everyone has his favorite, but

no one will dispute that the late 1940s and early 1950s were

Barks' golden years. There were masterworks to come, it's true,

but when you have been pursuing any subject for a decade, it's

hard to find fresh things to say. Past accomplishments hem you

in; wealth accumulated along the way must be sorted and reckoned

with. It's no coincidence that the Scrooge stories of this period

open inside the money bin on scenes of breakdown ("Tralla

La"), ennui ("The Seven Cities of Cibola"), and

illness ("The Mysterious Stone Ray"). As Barks was

fond of saying in later years, "The mind is not a bottomless

well, and mine is about pumped dry." Not until "The

Lemming with the Locket," which opens with a symbolic slamming

of the vault door, would the adventure tales take a new tack,

if not in subject matter, then in tone.

Having written about Barks

steadily for fifteen years, I find myself in a similar fix. Friends

tell me that I've recycled so many old articles of late, they

no longer look for the new ones. In a spirit that's part defiance,

part desperation, I have decided on a rash course. I shall critique

what is probably Barks' most famous and most perfect story, "Tralla

La." It won't be easy. Like the legendary Himalayan valley,

the tale is nearly impregnable. I have already published and

put behind me two analyses. If I am to say anything more, I shall

have to scale new heights.

You, like Donald and the

boys, are coming along.

Most critics pursue their

literary game (pun intended) with axes ready-ground. They know

what the story's about: it's about whatever cultural or political

issue interests them, and their job is to whack away at

the artwork until it submits to their paradigm. There's a use

for these busybodies: they get at things. In forty years Barks

has revealed nothing more than the fact that "Tralla La"

grew out of his desire to draw one billion of something--and

that, to use another phrase of his, is wind up the chimney. If

the modern theorist cuts away with skill and restraint, he can

shine some fascinating light into the dark corners of genius,

corners the artist might rather keep obscured. But there's always

a danger the artwork itself will collapse in a shower of chips,

leaving only the theory standing.

Other critics--among whom

I number myself--accord the artist a degree of political and

psychological privacy but still want to plumb his research, use

the story as a way of getting inside the workshop. Barks had

two sources for his Himalayan morality play: the Frank Capra

film of James Hilton's Lost Horizon, which provided the

germ of an idea; and a long, enthusiastic account of a trek to

Hunza in the National Geographic Magazine, which provided

everything else short of ducks. To recap briefly: at the northern

border of Pakistan, just under the rooftop of the world, perches

a tiny kingdom that could easily be Hilton's Shangri-La, an oasis

of apricot trees and green, terraced hillsides. The folk there

enjoy an isolated, peaceful, and Spartan way of life with no

great riches but no great hungers either--at least they did in

1953, when Jean and Franc Shor published their account of the

valley and Barks turned it into a Scrooge adventure. He must

have been drawn to the color photographs of fruit blossoms, rice

paddies, and a telltale V-shaped notch in the mountains. These

details all show up in his art, but the Shors' text is what really

sparked his story.

"Why should I have

a bodyguard?" the ruler of Hunza once asked his visitors.

"I have no enemies. Only once since I became Mir have we

been worried. Two years ago someone thought he had discovered

a rich vein of gold. Fortunately, it turned out he was mistaken."

It's plain Barks had this passage in mind when he described the

cliffs of Tralla La as "pure old rock! No gold or

jewels to contaminate the people!" Even the incident of

the honest rice farmer who retrieves Scrooge's bottle cap is

grounded in fact: a Hunza man once walked eight miles to return

Franc Shor's lost watch.

This mining in the Geographic

is a valuable exercise. It gives us the chance to watch a master

at work--and aren't most readers voyeurs? But it doesn't address

the crucial issue. Assuming that "Tralla La" speaks

to us, how does that happen? What makes it resonate in our minds?

Why do we collect it in first editions and reprints, read it,

reread it, and pester the artist to tell us what he ate for breakfast

the day that he wrote it? What is the story about?

On a narrative level,

"Tralla La" inverts the themes and threads of "The

Secret of Atlantis," its immediate predecessor. The ducks

travel to the roof of the world rather than its sunken depths,

pursue peace rather than riches, deflate a bottle cap's false

value rather than falsely inflating the worth of a coin, and

destroy an ancient civilization instead of leaving it intact.

The impulses of "Atlantis," from its half-page pie

fight to its final silly coda with Donald in the trash can, are

comedic. The impulse of "Tralla La" is tragic: a noble

quest and a noble society brought low. The story ends with paradise

nearly choked by bottle caps and Scrooge going into another nervous

breakdown.

I was irritated recently

to read an advertisement for the present edition which called

the comic a "textbook treatise on micro-economics."

Equally irritating perhaps was my own premise some five years

back, borrowed from Nathaniel Hawthorne, that Barks' story showed

us the degeneracy of the human heart. A Marxist critic would

probably tell you that "Tralla La" is about the destructive

effects of capitalism on a pre-industrial society. If we could

get Barks to open up about his private feelings in 1953, we might

discover that the comic is about stress, something he knew well

in the years following his divorce. How many other funny-animal

comics do you know that open with the hero having a nervous breakdown?

I know one, and it's also by Barks ("The Golden River,"

written four years later).

In 1984, when I published

my first major article on Scrooge, which grew out of a paper

on the ethics of collecting in Henry James' fiction, I received

a letter from a reader who identified as passionately with Scrooge

as I did with James' art patrons. "As a collector I am one

who uses beauty to distance myself from life," this duck

fan wrote. "The reconstruction of a happy childhood to avoid

the stress of a not quite as happy adulthood is paramount in

my comic collecting." He then proceeded to restate my arguments

with reference to his own life and anxieties, winding up with

the following observation: "As in 'Tralla La,' the ultimate

price of the collecting obsession is madness and the realization

that a collector can never escape the inner trappings of his

own mind."

What allowed this man

to connect with me, allowed me to connect with James, allowed

us both to connect with Barks? What makes a comic book set and

penned in the 1950s, built from scraps of travelogue and animation

gags, so vital and relevant today? It isn't the money fetish--tellingly

portrayed as bottle-capitalism--though that has fired America's

dynamos for more than a century. It's the emotion behind

that fetish. Working instinctively, Barks could reveal on the

comic page things he would never vouchsafe to an interviewer.

After his retirement, when it seemed there was no danger of his

having to illustrate the story, he wrote a brief scenario for

a new trek to the paradisal valley, stripped this time of its

glamour and called simply "Khunza" (a variant spelling).

His prefatory note says it all: "This is a tale of a great

need and a great fear."

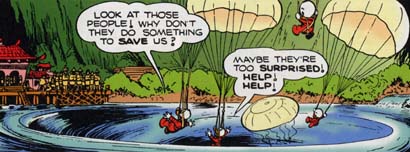

"Tralla La"

is about every man's desire to escape, to be at peace. It is

also about the ultimate frustration of that desire. Again it's

no coincidence that paradise, like the money bin and the human

mind, has chaos at its core, pictured this time as a roiling

lake smack in the middle of the valley. "Throw them in the

whirlpool!" is a cry that comes readily to the angry mob

of Tralla Lalians; the torrent is never far from their minds.

We recall the ante-bellum world of Plain Awful--another happy

valley--where only one crime was possible, one terrible law held

sway ("Lost in the Andes"). The natives of Tralla La,

like their cousins in the Andes, have learned to live with death

on their doorstep. They stretch a net across it, but even then

they fear an accident that might dam the whirlpool and flood

their homes.

This becomes the ducks'

one bargaining chip: to play on the fear that unites them with

all mankind. It's Barks' method, too, as storyteller: invoke

terror, but in ways palatable to a Disney audience. For instance,

we are distracted from the nastier implications of Scrooge's

breakdown by the comic spectacle of the old duck sleeping squirrel-like

in a tree. When we do fall into the whirlpool, the net is there

to catch us. Such deft double-shuffles allowed Barks to explore

human trauma in a way unparalleled among funny-animal artists.

Donald Ault, who taught

me to think of the duck comics as something more than newsprint,

put it best nearly thirty years ago. "'Tralla La,'"

he said, "is about the explosion of Nirvana."

Today

that phrase comes closest to expressing my own feelings about

the story. It's not just a charming, funny, slightly frightening

treatise on the impossibility of paradise, but an explosion for

everyone who reads it. It stops us in our tracks and makes us

want to attach ourselves to it, collect it, use it to explain

our lives, make it fit our critical structures. The story quite

simply is about its own emotional impact. All great art is.

Don't get me wrong. The

comic's prevailing cynicism could probably be traced back to

Barks' mood in 1953. Its charm can be attributed to scraps of

atmosphere and incident borrowed from the National Geographic;

who among us is not moved by the tale of the lost watch? And

yes, it is a treatise on economics that carries a lesson

for Marxists and capitalists alike. That explains why we study

the story, not why we read it.

Art is about emotion.

Our emotion.

Copyright ©

1996 by Geoffrey Blum

Drawing copyright © 2003 by Disney Enterprises

First published in Uncle Scrooge Adventures in Color,

No. 6 (July 9, 1996) pp. 25-26.

|

|

|

|