|

News and Views Archive: 2003 September.

SOME ENCHANTED

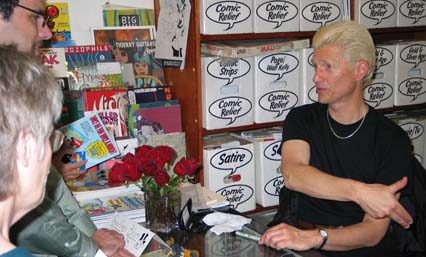

SIGNING It was a fitting venue

for Blum, who began collecting and studying Disney's duck comics

while an undergraduate at UC Berkeley. There he took courses

from Donald Ault, an authority on Carl Barks, the man who created

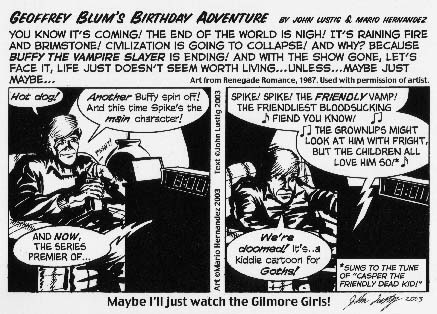

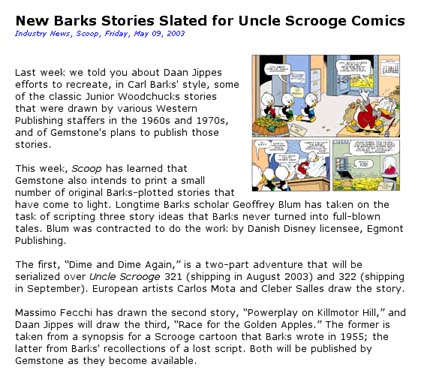

Scrooge McDuck. "And he is an industry," said Blum. "This is a character who's been around for many years, and he's going to be around many more. That's why I'm trying to pull him into the era of DSL and Goth discos. Kids read differently today; you can't rely on nostalgia to draw them in. You've got to find something they relate to. The trick is to do it with a light touch." Proprietor Rory Root added, "The French call comics the Ninth Art, but here the general public are still discovering that comic books have much to offer and entertain them." Blum arrived in a full-length black leather coat with a sorcerous-looking woman on his arm--clearly a Magica de Spell fan (check out Denise Pieracci's elegant and edgy line of clothing at Satin Shadow Designs). The store filled with fans and friends, and he was kept busy chatting and signing for nearly an hour beyond the allotted time. The grown-ups enjoyed a spread of wine and cheese, there were milk and cookies for the kids, and Rory kept the author's glass filled with cabernet.  "World Wide Witch" has recently been the subject of a heated Internet debate, with readers arguing about the story's computer jargon, allusions to Wicca, and its grounding of Duckburg in the present day. There was no grumbling at the party, however. As one reader put it: "I was very impressed by the crowds you drew." Well, that's the official version I penned right after the event, and there's not much to add. I was pleased to see a paragraph by Stefanie Kalem in the East Bay Express for August 20 (p. 41), publicity that I didn't actually have to write myself, though Ms. Kalem clearly drew on my first press release and my web site. It was disappointing not to have any children show up for Uncle Scrooge--not so much as one reluctant toddler dragged in by a well-meaning parent. A few teenagers lurked at the edges of the refreshments table, helping themselves to cookies and reading Pokemon books, but all the duck fans were over thirty. What's to be done about that, I don't know. After we closed down the signing and I autographed the remaining stock (and three cheers to Gemstone's John Clark and Steve Leaf for rushing us sufficient copies), Rory, Denise and her boyfriend, and I repaired to a nearby Indian restaurant. Since Indian for me is major comfort food (so sue me; I'm a nineteenth-century Brit), it was a grand finish to a grand day. This month's column is late getting launched because I've been unseasonably busy, what with a heat wave (you try working all afternoon in ninety-degree temperatures), new software to be installed, a new DSL line that went down for three days solid, and three more days spent in conference with my editor and project manager, who flew out from Denmark in the middle of the month. None of that interrupted my CD buying, but it has put a dent in my listening time. Still, one recording leaped from the stack and deserves immediate mention: Gustav Mahler. Symphony No. 6 in A minor. London Symphony Orchestra conducted by Mariss Jansons. LSO Live LSO0038. I have finally found a Mahler's Sixth to set against Leonard Bernstein's--no small achievement. It's Mariss Jansons' new live recording with the London Symphony Orchestra, and it's a winner. I've followed Jansons' career for twenty years now, since the advent of his Tchaikovsky cycle on Chandos, and I've seldom been less than impressed. The man is a master of orchestral color and expression. He's well nigh infallible at shifting between the dance tunes and the darker weather in Dvorák, Sibelius, and Tchaikovsky; his Respighi has the right blend of Renaissance brushstroke with Hollywood bombast; while his Scheherazade, by that ultimate colorist Rimsky-Korsakoff, is simply the best I've heard. Jansons can even engage me with composers whose pounding sounds I'd normally avoid, like Shostakovich and Stravinsky, because he makes me aware of so much more than the decibel level. But Mahler? Mahler's music requires an emotional heat and heart-on-the-sleeve shamelessness few can manage. Bernstein did it twice on record, first with the New York Philharmonic (Sony SMK60208), then with the Vienna Philharmonic (Deutsche Grammophon 427 697-2). Neither of those performances will be topped. Bernstein's pupil Michael Tilson Thomas is fine at articulating the score, providing signposts for us through its knots and twists and hammer blows, but with MTT it's all rather cool and detached. Noisy at times, but detached. I haven't heard his recent CD with the San Francisco Symphony, but I have heard him conduct the Sixth live, and I'd sooner have Arthur Fiedler on the podium. Even Pierre Boulez, another study in buttoned-down Mahler (DG 445 835-2), conveys more emotion than MTT. Mahler demands guts. Add to this the fact that Jansons' forays into Wagner and Brahms, at least on disc, have been less than thrilling, and the deck would seem stacked against him. You don't have to master Wagner in order to tackle Mahler, but it doesn't hurt. Mahler himself worshipped Wagner, and though he sneered at Brahms, the affinities are there. Jansons' 1992 disc of Wagner overtures never quite caught fire (no thanks to the dry acoustic provided; EMI 7 54583-2), while his recent Brahms cycle with the Oslo Philharmonic on Simax, though beautifully played, was--let's face it--underpowered. So I'm glad to report that he has found a road through Mahler's dark and thorny landscape. By adopting a pace that's urgent instead of the anguished tread favored by Bernstein, Jansons drives this symphony forward. Marches are tightly sprung, the Andante moderato sounds properly melancholy (though it's tender sadness rather than heart-rending), and horns for the most part are brisk and busy. Credit must go to the orchestra and to its engineers, for the digital sound really is glorious. There's something to be said for having strings less rich and burnished than the Vienna Philharmonic's: you hear more from the rest of the players. The tart, gamine voice of the violin (how Shostakovich!), hoots and growls on the brass (think of Peter and the Wolf), one xylophone pinging away insistently at the same note as other instruments rise to overpower it--they're all here, the soldiers and maidens and woodland sprites of Mahler's musical universe. And Jansons pilots us through, whipping up his team, striking sparks, getting scratched by overhead branches--but somehow never throwing a wheel. It's one hell of a ride. The first two movements, I admit, could heave and sigh a bit more; there are times when it's hard not to make comparisons with Bernstein. For Jansons, the Scherzo is where this symphony really takes off, so if he had to place this movement third in order to whip himself up to it, I'll go along with the now discredited arrangement. (Where'd he get that old-fashioned idea anyway? From his mentor Mravinsky?) The Finale starts out ominously and builds to a whirlwind; Mravinsky would be proud. The one thing I miss on this disc is the applause that must have rocked Barbican Hall following the final notes. I'd have been freakin' cheering. Color photo by Bryan Hastings August. UNCLE SCROOGE AUTHOR TO MEET WITH FANS Blum, who spent fifteen years writing criticism for collector's editions of classic Disney comics, is an expert on the Donald Duck family of characters. Three years ago, from his East Bay home, he began penning original stories for Egmont, Disney's Scandinavian publisher. His first two tales are finally available in American editions from Gemstone Publishing, and there are more on the way. "It's exciting, and a little scary," said Blum. "These are characters everyone remembers, but they need to be pulled into the twenty-first century if the comics are going to survive. I'm trying to do that while remaining true to spirit of Carl Barks, the man who created Scrooge McDuck. My first story introduces Scrooge to the power and abuses of the Internet. Many writers treat the old miser as if he were still living in the 1950s." Rory Root, proprietor of Comic Relief, agrees. "Often the public sees comics as either superhero epics for teens and adults or funny-animal books for the kiddies. They don't realize that a good story can cross genres and speak to all ages." Blum will meet fans and sign comics on Saturday, August 23, from 2:00 to 4:00 p.m. Comic Relief is located at 2138 University Avenue, near the downtown Berkeley BART station. For more information, contact Rory Root. That's it, then. We've built it; now let them come. The Comic-Con in San Diego was a big success for me. I got to see old colleagues from Gladstone Comics ensconced at Gemstone Publishing, schmoozed with friends like Dana Gabbard and John Lustig (creator of Last Kiss Comics), and met for two hours with my editor and his boss to hammer out a book project. Like other bad-boy wannabes, I traipsed around in jeans and black leather, trying to look sinister--until I realized just how many guys were doing the same thing. I may have to start wearing bright colors again. Below is John's comment on all this, done for my birthday back in April:  Overall I was struck by a feeling of camaraderie, a point brought out in Dana's panel on letter columns in the comics. Comic books, he averred, have traditionally appealed to the geeks and loners among us, but fandom gave us a way of connecting, and letter columns of the 1950s and 1960s showed kids that it was valid and adult to take an interest in cartoon fantasy. You weren't a deviant; you weren't alone. Today, alas, we have only chat rooms and posting boards where opinions fly around in a free-for-all. There's no sense of maturity or accomplishment from getting your observations into print; you just jump feet first into cyberspace. What impressed me most, however, was a talk by fantasy writer Neil Gaiman--specifically a moment in his question-and-answer session. Somewhere at the back of the room, a childlike female voice piped up: "I'm an artist and you are so my inspiration behind my career and I get these wonderful story ideas but many times I can't get started, I can't get out the first two pages and this is so frustrating and I was wondering what you do when this happens--does this happen to you, and how do you deal with it?" Or words to that effect. I couldn't see the speaker, but from the voice I'd have said she was fourteen. Gaiman didn't just fend that question, he gave it a level and considered reply, as if the questioner were no less deserving of respect than anyone else in the room. In short, he treated her like a grown-up. And I thought, "Damn! What a pro!" In the last few weeks, I've received some gripes about the fact that I posted Alberto Becattini's interview in Italian. There's a reason for that: while I could easily provide English copy for my own quotes, I'm not up to translating the rest of the text. Rest assured, most of my comments appear in fuller form in "That Old Duck Magic," and details of my life can be found on my Career page. On to this month's music review: Antonín Dvorák. Violin Concerto in A minor, Op. 53; Piano Quintet in A Major, Op. 81. Sarah Chang, Leif Ove Andsnes, Alexander Kerr, Wolfram Christ, Georg Faust; London Symphony Orchestra conducted by Sir Colin Davis. EMI 5 57521-2. I bought this CD for Andsnes' playing in the quintet, but it was the concerto that won me over. Despite orchestral sound that's thick and resonant--you notice at once in the opening tuttis--this is a performance that makes you realize what a great concerto Dvorák wrote. Chang's violin is very much to the fore, enabling you to follow every note that she plays. Unlike Itzhak Perlman, who can dash off the music with such apparent lack of effort as to make it sound glib, Chang unfolds and explores the score. This results in one or two passages where she seems to be laboring, as if to crank a bigger sound from her fiddle (try track 1, 7:42-8:03), but pays dividends at other times. Listen, for instance, to the cadenza, where she plays above a long-held note on the horn (10:37-10:59), so that from 10:52 onward, horn and violin are raptly holding their respective notes together. It's magic, and leads into an Adagio that's equally rhapsodic. In the Finale I would have liked some of Perlman's pyrotechnics, more kick and abandon to the Slavonic dances. Yet at 4:02, when the violin shifts into Dvorák's second dance, Chang's measured tempo points up the music's soulfulness. Throughout the concerto, Davis opts for tempi that are majestic and ruminative, more so than I'm used to hearing, but they suit this soloist and make me eager to hear Davis' recent recordings of the last three Dvorák symphonies (on LSO Live). I have one major quibble: Chang's tone can be thin (though the close miking compensates). It's an impression I had last spring, hearing her play in Berkeley; her instrument sounded wiry and was not projecting into the auditorium (Zellerbach Hall is notorious for its acoustic). Halfway through, she solved the problem by switching bows, and was delighted when I remarked on it after the concert. No more delighted than I: I had noticed the difference but was unable to pinpoint it till she explained what she had done. I'll be returning to this performance, which takes it place on my short list along with Salvatore Accardo (again with Davis, a performance of poetry and power which also puts across that horn effect, Philips 420 895-2) and Akiko Suwanai, a recent contender who takes the finale at breakneck speed but makes it work (Philips 464 531-2). Suwanai's Dvorák has flair, idiomatic backup from Iván Fischer and the Budapest Festival Orchestra, and spacious modern sound; you could do far worse than to pick up her CD. As for the quintet: I've listened three times now with pencil in hand. First I noted the presence of the exposition repeat--a feature I always enjoy, though Dvorák was no stickler for the practice. Again I found Chang's tone wiry. In some ways this works: where a sweeter or beefier violin might dominate, she allows us to hear her colleagues clearly; but when she plays forte, the sound can be tart. Andsnes interacts with her in true chamber fashion, distinct but never overbearing. His Dvorák is much like his Schubert: alert, limpid, and a bit cool. I'm not sure this coolness is an asset in the opening Allegro, where ensemble passages cry out for a gutsier approach. The more I listen to Dvorák, the more I recall Levon Chilingirian's comment on how tricky it is to sort out this composer's textures and find just the right tack in the seemingly simple melodies. The wistful Dumka fares better, and things really catch fire in the Scherzo; you feel that the players are finally letting their hair down. This energy carries over into the Finale, where occasional passages (typically slow ones) will take your breath away; rhapsody seems to be Chang's strength. Just listen to her and Andsnes lead into the final recapitulation (track 7, 6:21-7:06), with low, hushed notes on the strings behind them reminding you that Dvorák trained as a church organist. The climax is nicely crisp but doesn't quite have me leaping to my feet. Have I been listening too much to Martha Argerich and her fleet

and furious fingers? I checked a number of older recordings of

the quintet, searching for one that would bear out my preconceptions--and

came up empty-handed. Andsnes once called me a Dvorák

freak, but this time I have no clear favorite to plug. Clifford

Curzon with members of the Vienna Octet (Decca 421 153-2) comes

close in offering both heft and sparkle, but forty-year-old Decca

engineering can't compare with the sound EMI provides for Chang.

I remembered liking Jan Panenka and the Panocha Quartet (Supraphon

11 1465-2 131), but their Scherzo is leaden by comparison. The

Panocha's earlier recording with Monika Leonhard (Saphir INT

830.863) has more sparkle and a fine performance of the Op. 26

Piano Trio as fill-up--but try finding that disc today! Susan

Tomes on Hyperion may be your best modern alternative (CDA66796).

A close and resonant acoustic thickens textures in the Allegro,

but she and the Gaudier Ensemble get the third movement's hurdy-gurdy

effect just right and sprint like troopers for the finish line.

Till Argerich sets down a digital performance, I'll listen to

Tomes and keep listening to Chang and Andsnes. Despite my quibbles,

the newcomers have much to recommend them. July. Suddenly I'm on the move. After a decade writing essays and stories in seclusion, it feels good. With luck (and deft File Transfer Protocols), this page will move with me. Check here to read of work in progress and the occasional book-signing. Send in your comments (or howls of protest--there's a link on every page) and I'll try to respond to all but the most demented. Barring that, I'm always reading, always listening to music. I'll fill the page with record reviews if I have to. But for now the page itself is news. This is my web site's first facelift in three years, and everything's been tweaked. You'll find more art, fresh essays, an interview by Alberto Becattini (brush up your Italian!), and a feature in which I take you step by step through the process of scripting a comic book. Because of the turn my career has taken, I've geared the whole site toward Carl Barks and the Disney ducks. That's not to say I don't still accept the odd editing or consulting job, and the odder the better. But ghosts from the past have risen to claim me, and I'm a comic-book writer again. Once a Green Lantern, always a Green Lantern. So you'll find me this summer hanging with friends and colleagues at the International Comic-Con in San Diego. Normally I shy clear of such shindigs, but this time Egmont, my Danish publisher, has dangled a project that's too big and tempting to ignore. When I'm not conferring with the Danish contingent, you can run me to ground at Diamond Publishing's booth. Look for me there from July 17 through 19. After that, Comic Relief in Berkeley will host a signing party to mark the American publication of "World Wide Witch" in Uncle Scrooge 320. Since I began studying Barks as an undergraduate at UC Berkeley, the location is apt. When proprietor Rory Root and I have settled on a date, I'll post it here--or you can check Comic Relief's web site. Bring your friends and groupies. Come August and September, "Dime and Dime Again"--my completion of a lost Barks story--will be serialized in Uncle Scrooge 321 and 322. Read about it in Gemstone Publishing's press release, and be sure to visit Gemstone's web site.  As for those reviews I promised: try to hear Gianandrea Noseda's new recording of Prokofieff's Tale of the Stone Flower with the BBC Philharmonic (Chandos 10058). Prokofieff based this ballet on Pavel Bazhov's The Malachite Box, a collection of folktales from the Ural Mountains, and when I sat down last year to write a Scrooge story set in Siberia, this is the music that flooded my head. Mixed in with folk dances and some tip-tapping rhythms suggestive of gem-cutting is the "big country" sound that characterizes the composer's late works: soaring melodies that have you half expecting Ben Cartwright to come galloping over the range. You can tell Prokofieff enjoyed his vacations in the Urals. It's a shame his visits to the Disney Studio in the 1930s didn't bear similar fruit, for he was a master orchestrator and would have been a natural to work on Fantasia. In fact, you get the impression that Noseda is more interested in the twists and turns of Prokofieff's scoring than in making a case for this neglected ballet as music. Bolstered by rich recorded sound, his expansive conducting allows a wealth of orchestral detail to shine, but at the expense of momentum. It's one thing to perform this score at dancing speed, another to let it sprawl. Under the baton of Michhail Jurowski on CPO (999 385-2), the ballet acquires more point and thrust without ever seeming rushed. While Jurowski doesn't exactly caress detail the way Noseda does, his engineers provide air around the instruments, so that the orchestral sound (as opposed to the conducting) becomes spacious. His North German Radio Philharmonic even feels more authentic than the BBC players, with growling brass in the Russian manner and just the right kick to the folk tunes. There's kick to the jewelers' music, too, whereas Noseda tends to drag out Act I as if to remind us that his sculptors and miners are oppressed serfs. Nowadays that may be politically correct, but Prokofieff rode herd on his original choreographer to tone down just such socialist-realist touches. It's Jurowski's performance

I'd want to live with, returning occasionally to Noseda for the

imaginative glimmers he brings to Acts II and III; there's never

any doubt that he's in control, shaping the music for us. Either

set would be a marvelous way to scrape acquaintance with the

Mistress of Copper Mountain, who will still be guarding her stone

flower when Uncle Scrooge comes calling in "Quest for the

Golden Tusker." Copyright © 2003 by Geoffrey Blum |

|

|||||

Copyright © 2003 by Geoffrey Blum