Wind from

a Dead Galleon "Well, so what?

It's a bunch of treasure,

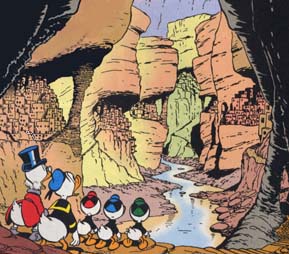

Yet for all the fuss and fan worship, it seems to me that "Cibola" is a story in which nothing much happens--nothing, that is, until the last three pages, when the pent-up energy of the tale is released in a single explosive panel. Until then we are treated to elements of a good adventure, but in a very leisurely fashion. Scrooge sets out not to discover Cibola but to grub for arrowheads as a way of relieving his boredom. The gold relics that spark his real quest are unearthed by accident when a clay pot breaks. With the appearance of the Beagle Boys, McDuck's leading foes, we might expect the plot to pick up pace, but the burglars also seem out of their depth. With no money bin to assault, they eavesdrop and follow rather than confronting the ducks head-on. When paths cross in the desert, it's by chance, and the Beagles do not press their advantage; they steal the ducks' water and move on. When ducks and Beagles meet a second time, our heroes are simply seized and imprisoned. Each encounter is over in half a page. The ghost ship that points the way to Cibola also appears by chance, and all it does is sit in the desert. It's been sitting there 400 years! If you think this assessment harsh, consider what Barks did with similar plot threads in later stories. The phantom ship that leads to the hoard of "The Flying Dutchman" is a robust and bellicose spook, a kind of storm god to be cursed one moment and placated the next. By the end of the story Barks has explained away the apparition in terms of pack ice and mirages, but that doesn't diminish the name-calling edge in his drama as the ducks struggle against the Dutchman, whom they dub "ghostly bully" and "our pal." By the same token, "The Money Well" keeps everyone's adrenaline flowing through a series of deliberate confrontations with the Beagles, a war of wits in which taunts and tricks are traded on a regular basis. Emotionally this is very satisfying, as Scrooge observes at story's end. In "Cibola" there is no discernible conflict, no Glittering Goldie or Chisel McSue to grapple with. There isn't even a moral crisis of the kind that pervades "Tralla La," though we hear a note of tragic regret for the fate that overtook the Indians who originally inhabited Cibola. This is the first in a new breed of story, the first Uncle Scrooge treasure hunt, and it's plain Barks was feeling his way--which is not necessarily a bad thing. The comic is constructed quite skillfully to make the reader grope along with Barks and the ducks, puzzling out a path across the desert. When the preliminary business with arrowheads is over and the story actually gets rolling, it unfolds like a parchment map or the account of an archaeological trek in the National Geographic Magazine. Our pleasure derives not so much from reaching the Seven Cities as from moving observantly toward them. Barks' own interest in Cibola was sparked by a visit to his friend Al Koch, manager of the welfare office in Indio, California. Koch, who was something of an authority on local Indian tribes, took the artist to "a place on the Thousand Palms Road where an ancient Indian trail wended over a mesa. There we saw rings of stones, cremation sites, and most of all worn steps up the far side of the mesa that indicated the trail had been used for centuries by traders from the Arizona tribes." That evening, over "copious draughts of bourbon and ale," Barks blocked out the opening pages of his new Scrooge adventure. As a form of acknowledgement he drew Koch into the story, kicking the Beagle Boys out of his office. The rest of the comic coalesced around a yarn Barks overheard in a restaurant, where a rancher was holding forth about seeing the Lost Ship of the Desert after a heavy windstorm. Barks had a feeling the rancher himself was a bit of a windbag, but he headed for a library to check out the facts. What he came up with was a wealth of surmise and scattered history that could be woven into his comic. "Little accounts had cropped up in the paper every once in a while of people who were delirious from thirst who saw the ship. I found that at one time it was believed to have been a ship lost from a survey party going up the Colorado, and at another time that it was believed to be a flat-bottomed barge that got picked up by a tidal wave generated by an earthquake. I figured I could go to town on that idea because nobody could say I was wrong." To lend his version credibility, he invoked the name of an actual Spanish naval captain, Francisco de Ulloa. The houses and kivas of Cibola he borrowed from a photograph in the National Geographic. "The tale results from more research than I usually devoted to my comic work," Barks admitted in later years. It shows. With the exception of the Geographic photo, the artist was drawing on verbal sources that relied on weight of information to engage a reader's interest. On the comic page this translates into rather cerebral sequences in which the ducks themselves do research, reading the Woodchucks' Guidebook, the sandy topography, the ship's log, and the Indian pictographs. Only the cinematic quality of Barks' desert scenery brings these panels to life. The historical characters are long gone, and they were less actors in the drama than victims of flood and sickness. By the time the ducks appear, Captain Ulloa and the canyon-dwellers have dwindled into spectral voices preserved in the logbook and pictographs. "Cibola" is the one Scrooge adventure in which the lost world, though it remains intact for sightseeing, is quite dead. No Larkies, Peeweegahs, or pygmy Arabs lurk in the ocotillo to challenge the ducks' invasion of their turf. At some level Barks must have realized this. In a desperate attempt at legerdemain, he created a spectacular climax to distract us from the static quality of his first twenty-five pages. He blitzed the Seven Cities, nearly killed his treasure hunters, and in fact wiped out their memory--the very faculty of research and storytelling. As a result the adventure comes crashing to a halt, leaving ducks, Beagles, and readers shell-shocked. Never before had the artist imposed such a full stop on one of his comics. Five years later, as if to prove the worth of his plotline after all, Barks reworked it as "The Prize of Pizarro." Again we follow the ducks up an ancient treasure trail to an Indian stronghold; again they find a golden hoard protected by a doomsday weapon. But what a difference in tone and pacing! By moving the Spanish galleon up front and introducing the logbook--in this case an army captain's letter--on the third page, Barks not only gets the adventure off to a brisk start, he gives the ducks an opportunity to interact with history rather than researching it. In fact, the letter becomes integral to the action. Scrooge reads it out a line at a time while his nephews cavil and comment, just as they did with the Dutchman. Pizarro's soldier might almost be there egging them on. An even more animated exchange takes place with the Indians, who are very much alive in this story. Though our heroes never meet them face to face, the reader is privy to a continuing dialogue of expectation and surprise as the Incas watch from the rocks, the ducks trigger one booby trap after another, and both parties react. It's a rich source of wordplay and laughter, elements conspicuously lacking in "Cibola," and it is significant that Lucas and Spielberg borrowed equally from "Pizarro" for their third Indiana Jones film. Even the famous trap in Raiders bears a sneaking resemblance to the Incas' Bridge of the Roaring Skull Cracker. Yet one tends to recall the more destructive weapon triggered by the emerald idol. Why? Having faulted "Cibola" for its slow pace and lack of human drama, we have to concede that it, not "Pizarro," is the tale fans remember. Last month, when I wrote that art is about emotion, I didn't expect to fall back on this dictum so soon. But it's true: something in that moccasin-beaten trail on the Thousand Palms mesa spoke to Barks, lodged in his mind like an arrowhead, and drew legend to it. In the same way, Raiders was a foregone conclusion the minute Lucas and Spielberg saw Barks' emerald idol--the one false bit of archaeology in an otherwise superbly researched story. For them it didn't matter. That statue crystallized all the thrills of pulp fiction into one shining image which eventually gave birth to three Indiana Jones epics. Emotional resonances are what carry "Cibola," cause scenes and fragments to linger in our mind long after the original comic has found its way to the dustbin or the collector's mylar bag. Joy of discovery, relief at finding a trickle of muddy water, the eerie thrill of treading a weathered deck and turning pages in an ancient logbook--these feelings are as vivid and intangible as the desert wind. It's a tribute to Barks that he was able to invoke this wind with such power that it overcame his occasional shortcomings as a storyteller. Copyright ©

1996 by Geoffrey Blum |

|

|||||

Copyright © 2003 by Geoffrey Blum